History of Spaceflight

Origins The first rockets were invented by the Chinese, but the exact date is not known. What we do know, from the chronicle known as the T-hung-lian-kang-mu, is that in 1232 the Chinese used "arrows of flying fire" to repel a Mongol siege of the city of Kai-fung-fu.1 From the description it is clear that these are small rockets, not merely bow-fired arrows carrying flammable substances. These were solid-fueled rockets, using black powder (also known as gunpowder, once guns were invented, sometime after 1300) similar to large fireworks still used today. How long prior to 1232 they were invented is a matter of dispute.

The Mongols learned the technology of gunpowder and rockets from their (violent) interactions with the Chinese, and within a few decades after 1232 rockets appeared in the Arab world and even as far as eastern Europe. An Arab writer, Hassan er-Rammah, in 1280 describes a design for a rocket-propelled torpedo (to be used on the ground, apparently, rather than the water), but there's no record of it ever being used. Despite that dramatic innovation, improvements in aerial rockets were very gradual improvements in the propellant (the gunpowder) and the shape of the molded propellant inside the rocket body. The rockets used by the British in the War of 1812 against the U.S. Fort McHenry in Baltimore ("The rockets' red glare...") were not dramatically different than the Chinese rockets used in 1232. One hearteningly peaceful use of rockets during the 1800s and early 1900s was the line-carrying rocket used in saving the crews of stranded ships. Ships run aground on reefs, rocks and sandbars during violent weather were often dashed to pieces, and the crews lost within sight of helpless lighthouse keepers and lifeguards on shore. Lifesaving stations (such as those along the North Carolina coast) used small rockets to fire ropes to stranded ships, along which sailors could pull themselves or small boats to safety.

Despite all this gradual progress, the rocket would never realize its full potential until the solid fuel was replaced with liquid fuel. Liquid fuel allows for a critically important feature: control. In a liquid-fuel rocket, tanks hold the fuel and oxidizer, and pumps move them into a combustion chamber where they are exploded. The resulting high pressure pushes the exhaust gases out the back and pushes the combustion chamber — and the rest of the rocket — forward. This is much more complicated than a solid-fuel rocket, but those pumps can be made to operate fast or slowly, and valves in the pipes can be opened and closed. In short, the thrust can be throttled up or down.

The invention of the liquid-fuel rocket would finally come in the 20th century.

Robert Goddard

- American, 1882-1945

- Invented the first working liquid-fueled rockets, working in the

late 1920s and 1930s. His early work was in Massachusetts, where he

was a physics

professor at Clark University in Worchester, but later moved to the open

spaces of New Mexico to continue his work.

Goddard with the first liquid-fuel rocket, March 1926 in Massachusetts.

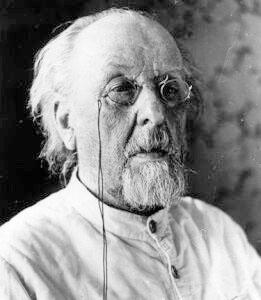

Konstantin Tsiolkovsky

- Russian, 1857-1935

- Developed much of the vision and mathematics of future space flight.

- Never built any actual rockets.

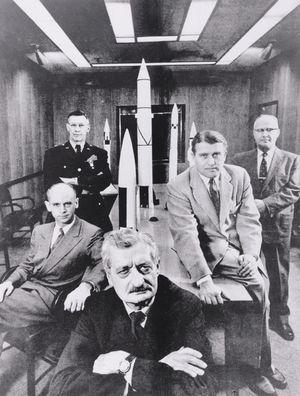

Hermann Oberth and the VfR

- German, 1894-1989

- Started working on rockets and spaceflight in the 1920s as one of the founders of the Verein für Raumschiffahrt (VfR - "Spaceflight Society"), developing theory, engineering and vision for space travel.

- Flew his first liquid-fuel rocket in 1929.

- The VfR was a group of amateur rocket enthusiasts in Germany that conducted much practical engineering development in the late 1920s and early 1930s. Many VfR members formed the nucleus of rocket expertise used by Germany in WW2.

- Although Robert Goddard was the first to develop liquid-fuel rockets, the VfR surpassed him by the late-1930s, especially once the German military started funding rocket research in 1932. Rocketry developments in the U.S. and Soviet Union after WW2 benefited greatly from emigree German scientists.

World War 2

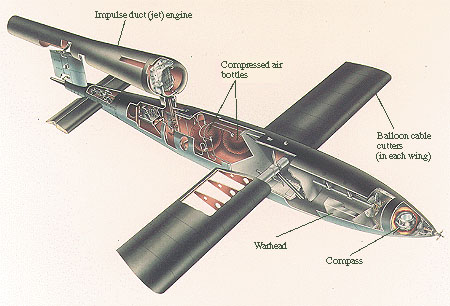

Well before WW2, the German military recognized the potential of rockets. During the war they founded a development center at Peenemunde. Rockets developed there were not ready for operational use until the last year of the war, however, after the D-Day invasion of Europe. The V1 was a winged missile (a pilotless aircraft, or what is usually called a cruise missile these days), about 2400 of which hit London, killing about 6,000 people and injuring another 18,000. They were unreliable, and also slow, so relatively easy for British fighter planes and anti-aircraft artillery to shoot down. Not so the V2, a ballistic missile with 300 mile range. Over 3,000 of them were launched — about half into Belgium, a bit less than half into London, and most of the rest into recently-liberated parts of France.

V1

.png)

V2 (click diagram for better resolution)

Here are some movie clips of V2 test launches during WW2. Notice Werner von Braun (about 29 seconds into the video) who later made major contributions to the U.S. space program.

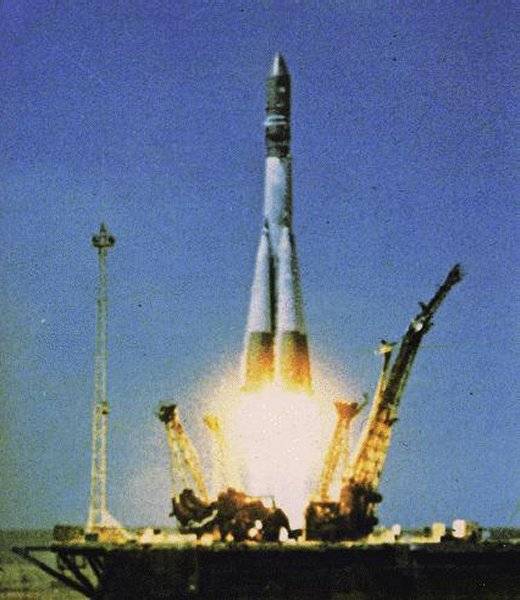

IGY, Sputnik and Explorer 1

The period July 1957 to December 1958 was, by international agreement, designated the International Geophysical Year (IGY). Participating nations resolved to conduct coordinated research in meteorology, seismology, oceanography, the arctic regions, geomagnetism, aurorae, cosmic rays, solar activity and the upper atmosphere. Both the US and Soviet Union planned to launch orbiting satellites, which had never been done before. The U.S. satellite program was making progress, but was not a priority. The Soviet Union succeeded first, launching a satellite called Sputnik ("companion") on 4 October 1957. Sputnik contained only a radio transmitter that beeped as it circled the world. The international public reaction surprised both the U.S. and Soviet governments, and was a propaganda coup for the USSR. This triggered the "space race", an intense competition between the US and USSR for superiority in space capabilities and acheivements. The first US satellite, called Explorer 1, had been designed but the program had been cancelled in favor of another program called Vanguard, which then ran behind schedule. After Sputnik, the Explorer program was revived. The satellite was built in 84 days, was launched on 31 January 1958 by a Juno I rocket, and discovered the radiation belts that surround the Earth.

Sputnik 1 (above); Explorer 1 (below)

Yuri Gagarin

The Soviet Union launched the first human into orbit, Yuri Gagarin, aboard Vostok 1 on 12 April 1961.

Huntsville AL newspaper headline announcing the first human in space. (Click for larger, legible version.)

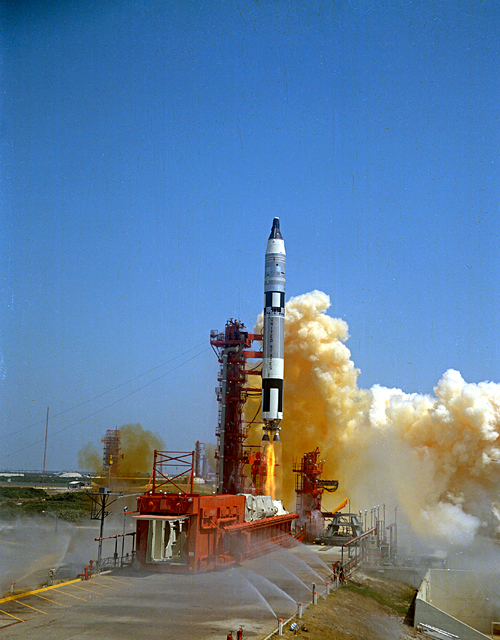

The Mercury Program

- one-astronaut capsules launched atop Redstone and Atlas rockets, and return by parachute, "splashing down" into the ocean

- each capsule was used only once

- six piloted flights, 1961-1963

- The first US human flight was by Alan Shepard, launched 5 May 1961 atop a Redstone rocket. It was less than a month after Yuri Gagarin's flight, but was only suborbital (i.e. the rocket went on a ballistic trajectory, up and down, rather than orbiting the planet.)

- The first US astronaut in orbit was John Glenn, launched 20 February 1962 atop an Atlas rocket. Here's a short video.

X-15

Forgotten by most people, the US Air Force built and flew a rocket-powered airplane that reached altitudes meeting the international standard definition of space (an altitude of 100 kilometers) on several flights. The flight program ran from 1959 to 1968. The X15 could reach speeds of 2000 meters per second, more than 4 times the speed of sound, but nowhere near the 8000 m/sec needed to reach orbit. A follow-on craft, the X-20 Dynasoar, was to be capable of reaching orbit but was cancelled in late 1963.

Gemini program

- two-astronaut capsules

- 10 flights, 1965-66

- was important transitional program between the first flights and the Apollo moon program. The skills of long-duration flights, spacewalking and orbital rendezvous, crucial to the success of Apollo program, were first learned during the Gemini flights.

Here a short video of Ed White's spacewalk, the first of the U.S. program, during the Gemini 4 flight.

Apollo program

- Goal set by President John F. Kennedy in 1961, to land astronauts on the Moon by the end of the decade. Watch his speech about the lunar goal, given at Rice University.

- Audio only, click here

- eleven manned flights as part of the moon-landing program, 1968-1972

- six successful moon landings: Apollo 11, 12, 14, 15, 16, 17

- one failure (Apollo 13) but crew returned safely to Earth. Clips from the movie Apollo 13 set to inspiring music. (Without music: launch, explosion & reentry)

- leftover hardware was used for the Skylab program (1973-4) and Apollo-Soyuz test project (1975). Skylab was in orbit until it reentered the atmosphere in 1979.

- other movie clips:

- departure of Apollo 17 LM from the lunar suface

- Apollo 17 CM splashdown in the Pacific Ocean

The Soviet moon project was, despite Soviet secrecy at the time, in a direct race with the U.S. The program was underfunded and mismanaged, however, and as a result suffered a series of fatal accidents. In the end, the Soviets were not close to being able to launch a successful crewed flight before the Americans. After the Apollo landings the Soviet program was cancelled and not publicly acknowledged until 1989.

Here's a detailed history from the Federation of American Scientists.

Space stations

International Space Station (currently under construction)

Here's the NASA homepage for the ISS program. It includes links to find when you can see the ISS overhead at your location.

Skylab (US): built from leftover Apollo hardware, and home to three three-person crews. The last crew lived aboard for three months, ending in February 1974. NASA hoped to use the new Space Shuttle to boost the abandoned Skylab's decaying orbit, but the Shuttle development program took longer than planned and in 1979 Skylab reentered Earth's atmosphere and was destroyed. The first Shuttle flight came in 1981.

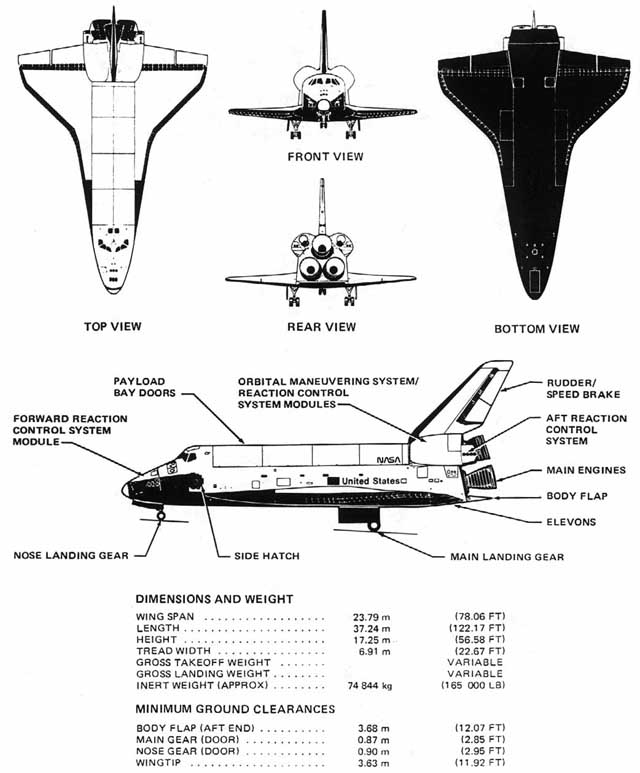

Space Shuttle

- Can only reach low Earth orbit (i.e. a few hundred miles up)

- By flying reusable spacecraft that landed on traditional runways rather than in the ocean, the hope was to make access to space far less expensive.

- Four shuttles were originally built (Columbia, Challenger, Discovery, and Atlantis), plus one prototype (Enterprise) that was used for glide tests in the atmosphere but never launched into space.

- The first flight was in 1981, by Columbia.

- Videos

- STS-108 launch: notice the gimballing (tipping/tilting motion) of the Shuttle main engine nozzles.

- STS-112 launch: cool video from a camera mounted on the outside of the external tank.

- After the 1986 Challenger explosion, a replacement shuttle (Endeavor) was built. Columbia was destroyed during reentry on February 1, 2003.

- Scheduled to be retired in 2011.

Those Who Gave Everything

Apollo 1 crew

Challenger, 1986. NASA tribute and data page. Short video.

Columbia, 2003

National Geographic Channel documentary.

Constellation program

- New spacecraft in development, to replace the Space Shuttles and enable a return to the Moon and later flights to Mars.

- Described as "Apollo on steroids", but also reusing some elements of the Shuttle program.

- First flights currently planned for 2015, with flights to the Moon by 2020.

- NASA Constellation homepage

As of early 2011, the future of the Constellation program is uncertain. The Obama administration wants to cancel Constellation, instead promoting commercial companies to run launch services to low Earth orbit. This would free NASA to focus on cutting-edge exploration. Congress is still negotiating with the executive branch about the future direction of the U.S. space program.

Projects That Never Happened

Planetary probes

Here is a Wikipedia overview of different types of space probes, plus a timeline of solar system exploration and a catalog of all solar and interplanetary probes.

Notes:

1. From Ley, Willy, Rockets, Missiles & Space Travel, Viking, 1957.